|

|

|

The Films of David Lynch Authorship and the Films of David Lynch Introduction Chapter 1: Eraserhead Chapter 2: Elephant Man/Dune Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Chapter 4: Wild At Heart Conclusion Matt Pearson 1997 50 Percent Sound Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Conclusion Philip Halsall 2002 Bibliography Resources |

|

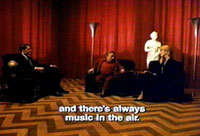

Chapter 1: Eraserhead Defining 'Auteur'The concept of the "Auteur" has its origin in a 1948 article by Alexandre Astruc in the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema. In the simplest sense it proposes the director as the "author" of a particular film and is identified by a consistency of visual style and thematic pre-occupations across a body of work. Of course, this approach to film had its criticism, much of which is dealt with over the next four chapters. First there was dispute as to the director's overall influence as film is clearly a collaborative process, even in the smallest of productions, and to elevate the status of the director is to belittle the contributions of other creative personnel such as the cinematographer, the editor, the sound man and the actors. This is countered by crediting the director with the responsibility of choosing his/her crew. This is not always the case as the producer is often responsible for assembling the creative team, especially within the studio system. This tension between producer and director is touched upon in Chapter 2 with the relationship between Raffaella de Laurentiis and David Lynch while working on Dune. Andrew Sarris, in "Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962", demanded a more detailed definition of the term, transforming "la politique des auteurs" into an auteur "theory". He proposes three premises to spot an auteur, the first is "the technical competence of a director as a criterion of value", he says "a great director has to be at least a good director". The second premise is "the distinguishable personality of the director as a criterion of value. Over a group of films, a director must exhibit certain recurring characteristics of style, which serve as his signature". The third premise is a more mystic interior meaning: "Interior meaning is extrapolated from the tension between a director's personality and his material. This conception of interior meaning comes close to what Astruc defines as mise-en- scene, but not quite. It is not quite the vision of the world a director projects nor quite his attitude to life. It is ambiguous, in any literary sense, because part of it is imbedded in the stuff of cinema and cannot be rendered in non-cinematic terms."This is a vague premise suspiciously ambiguous and perhaps ineffable but, in my opinion, achieved Lynch's work. It is a combination of this and the second premise I propose to define as "Lynchian". Lynchian Theme and StyleMichel Chion, in "David Lynch", says "In the beginning, there was not an author, just a film: Eraserhead". Eraserhead is very useful in the context of this study as it can be seen as a definitive text in regards to Lynch's stylistics and thematic pre-occupations. The film's story is very simple (the script was only 20 pages long) but the use of stylistic symbolism is very detailed and complex. Being so simple in structure and defying any categorisation of genre, it can be used as a control sample in our examination of Lynch's other films. Chion says "There is nothing more common nowadays than an auteur. Auteur films, which create their auteur, are rarer stuff". Eraserhead created Lynch, the auteur. It took Lynch five years to make Eraserhead, his first full length feature, and in interviews he has often described it as his "perfect" film. It is the story of Henry, and the claustrophobic horror of his day to day life. It opens with Henry's head superimposed over a featureless planet. Inside the planet resides a workman. Henry opens his mouth and a worm-like creature emerges. The workman starts his machinery; his first lever sets the worm in motion, his second lever reveals a water filled hole in the earth and a third lever catapults the worm into the hole. The camera emerges from this hole into a bright white light. We then enter Henry's life, we see him walking home and taking the elevator to his apartment. His apartment is dark, minimally equipped, with a window that looks out onto a brick wall. Henry is invited to Mary's for dinner with her family. He is offered a shrunken chicken to carve, which moves and bleeds when Henry skewers it with his fork. It is revealed that Henry and Mary have had sex and that there is a "baby". The baby is another worm-like creature. Henry and Mary share his apartment for a while until the baby's crying drives her back home. Henry falls asleep thinking of the woman who lives in the apartment opposite and wakes to find the baby is ill. Henry is now bound to his apartment, as the baby cries if he attempts to leave. Then follows a prolonged dream sequence. Henry falls asleep staring at his radiator. In his dream he enters the radiator to find a woman, with grossly swollen cheeks, dancing on a small stage within. Worm-like creatures fall from the ceiling and are crushed underfoot in time to the music. Back in Henry's room, Mary has returned but she writhes in a bed full of worms. In an animated sequence a small worm wriggles away. There is a knock on the door and his neighbour emerges from the dark. She seduces Henry, their bed becoming a bath of milk into which they both sink. Back in the radiator, the swollen woman sings an invitation: "In heaven, everything is fine". Henry steps onto the stage, takes her hand and is consumed by a bright light. The workman appears and a wind brushes the worms from the stage. Henry finds himself in a dock, his head flies off and the baby's head replaces it. The head then falls from the sky, is collected by a boy who takes it to a workshop where it is made into pencil erasers. On waking up, Henry tries to visit his neighbour but she isn't in, the baby laughs at him. He hears her return and sees her in the hallway with another man, she sees Henry with the head of the baby. Henry then cuts the baby's bandages and pierces the baby's heart killing it. The lights flicker and the sockets spark. A hole is blown in the planet, the workman struggles to stop his machinery. Henry, in a bright light, embraces the swollen woman and the picture cuts to black. I don't intend to dwell too long on the interpretation of these events as it is best left up to the individual. It's safe to assume the workman represents God and the swollen woman, Death. When Henry stares at his radiator (where Death resides), as he does on several occasions, he is considering suicide. The worms are a reference to the original sin, the reproductive process, the worm cast into the hole at the beginning being the conception of either Henry or his baby. In the dream sequence he dreams of adultery with his neighbour, death (the invitation of the swollen woman), judgement (the dock) and the absolution of his sins (the worms swept away and his head made into an eraser). The film ends with Henry killing his burdensome child and then killing himself. Just as Henry's eraser is tested by making a mark and rubbing it out, Henry is creator and destroyer of the baby, the planet he occupies and ultimately himself, implying this whole world existed for Henry alone. Viewed through Henry's eyes, and probably only existing in Henry's head, it is an expressionist representation we see on screen, with Henry's perception of events hideously exaggerated - the fidgeting of Mary, the grotesque disease suffered by the baby, the fixed grin of Mary's father. Eraserhead introduces two of Lynch's principle themes. Firstly, the concept of other parallel worlds accessed via our dreams. In Eraserhead it is the world behind the radiator, in The Grandmother (Lynch's 34 minute short film made in 1970) it is the boy's attic. In Twin Peaks the concept of parallel worlds is most blatantly explored with The Black Lodge, where Bob resides, infiltrating reality as well as being accessible via the dreams of Cooper and Laura. Dreams as a motif form a thread through his films; the extended dream sequence in Eraserhead, in Dune, Paul dreams of his future, the mantra being "the sleeper must awake". In Wild At Heart sailor dreams of the good fairy, The Elephant Man dreams of his mother, and in the pilot episode of Twin Peaks, Bobby assures Norma he will see her in his dreams. "In Dreams" is Frank's theme song in Blue Velvet. The world beyond the radiator is given a very theatrical setting; the stage, the spotlight and the surrounding curtains. This idea of performance recurs also; it is a stage on which the Elephant man is displayed, where Dorothy sings in Blue Velvet, and Julee Cruise in Twin Peaks. When Sailor dances in Wild At Heart it is very exaggerated performance, as is Lil's dance in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. The curtains are a motif: the title sequence of Blue Velvet, the decor in the Black Lodge (the floor design mimicking that of Henry's apartment block) and the academians view of the Elephant man; silhouetted through curtains. Nadine, in Twin Peaks, is obsessed with the smooth running of her drapes. The curtains also link us to night-time, when most of Lynch's action is set, especially in Eraserhead and Blue Velvet. Spotlights are used to highlight certain elements of mise-en-scene, with unnatural pools of light featuring strongly, especially in the black and white films. These pools of light are often cast by standard lamps which are compulsory furniture in Lynch's world. Lynch's second major theme is his obsession with biology. Each worm-like creature in Eraserhead manages to resemble both a sperm and an umbilical cord. This image becomes a motif, for example, when Bobby Peru's head is blown off in Wild At Heart, it is in a stocking, trailing behind it as it flies. Dune features giant phallic sand-worms. The sexual connotation of the worm motif is blatant. Lynch portrays sex as unpleasant and problematic, if in Eraserhead sex is undignified and dehumanising, in Blue Velvet it is animalistic and violent. Henry's desire for his neighbour prompts his baby's illness. The worm cast into the hole at the start of the film is the catalyst of Henry's suffering, ultimately resulting in his death (the machine is started but cannot be stopped). The chicken symbolises the sex act, it lies prone with legs in the air until Henry penetrates it with his fork and it begins to struggle and bleed. The chicken is offered to Henry by Mary's father, as if he were offering his own daughter. There are also the unwelcome advances of Mary's mother, a pseudo-Freudian element which features in The Grandmother, Wild At Heart (Marietta's advances on Sailor), Twin Peaks (Leyland raping his own daughter) and is explored to its extreme in Blue Velvet with the Oedipal "family" of Jeffrey, Dorothy and Frank. Lynch is particularly fascinated by the disabled, deformed and grotesque variants of biology, witness the swollen cheeks of the woman in the radiator, the scarring of the workman and the numb arm of Mary's father. Later, the One-armed man would be a principle character in Twin Peaks. The Elephant Man showed deformity to new extremes. In Dune, a feature extraneous to the novel was the Baron's hideous skin disease. Blue Velvet's mystery began with a severed ear. Even the way he shoots his actors distorts their natural biology, Laura Dern's sobs in both Blue Velvet and Wild At Heart contort her face cruelly. Urination is a favourite bodily function, from The Grandmother's bedwetting, Dune's recycling of bodily fluids, Blue Velvet's over-consumption of Heineken, to Bobby Peru's constant pissing in Wild At Heart. In Twin Peaks, Cooper and Major Briggs take time out to enjoy the 'heavenly pleasure' of peeing in the woods (episode 17). Lynch also has a fascination with the mouth; Duke Leto, in Dune, deals death with a poisoned tooth, Bobby Peru in Wild At Heart is a dental nightmare. Lynch's women bare their teeth in pleasure after being struck; The Reverend Mother in Dune, Dorothy in Blue Velvet, and Marietta in Wild At Heart. Close-ups focus on mouths - the baby in Eraserhead, Dorothy in Blue Velvet, a zoom into Leyland's screaming mouth in Twin Peaks (episode 11) and Mrs. Tremmond eating creamed corn in Fire Walk With Me. Food and drink are fetishised, from the chickens in Eraserhead, via the comparisons of beer taste in Blue Velvet, to Agent Cooper's obsession with coffee and cherry pie. Lynch's third major theme is best illustrated by the opening sequence of Blue Velvet. A sequence of shots paint a picture of the small town in which the film is to be set; red roses by a white picket fence, gardens, a fireman waving from his fire-truck, a school crossing guard, a man watering his lawn. But then the man with the hose-pipe (held at groin level, the urination fetish again), suffers a heart attack and collapses, his dog continues to frolic in the jet of the hose while the camera drifts down into the grass upon which the collapsed man lies. Beneath the grass, dark insects, in monstrous close-up, feed voraciously. This metaphor could apply to not only Blue Velvet but equally well to Lynch's subsequent work, Wild At Heart and Twin Peaks, the idea that under the cosy facade of the small town lies a seedy underbelly. Blue Velvet could probably be regarded as Lynch's second 'auteur' film as Chion defined the term. The rest of the film is expanded in Chapter 3. Timothy Corrigan, in 'A Cinema Without Walls' describes Blue Velvet as set in a "locale that appears so extraordinarily strange because it is so extraordinarily familiar." Lynch creates an idealised community, not so much with surrealism, but with a 'hyper-realism' (this again is discussed further in Chapter 3). He utilises conventions of 50's teen movies; the locations (coffee shops in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks), automobiles (Wild At Heart especially), teenage love (Sandy and Jeffery in Blue Velvet, Donna and James in Twin Peaks), the music (Elvis is the basis of Sailor's character in Wild At Heart), the dress and the attitudes (Bobby Briggs in Twin Peaks seeming an anachronistic James Dean for the 90's). He presents a Happy Days/American Graffiti nostalgia to the point of parody, to give a contrast to the dark 'other world' that is inevitably co-existent. Small town evil is the structure upon which the narratives of Blue Velvet, Wild At Heart and Twin Peaks are based but the idea of the facade of polite society, without the 50's stylistic codes, also features in Eraserhead(the dinner at Mary's), The Elephant Man(the sick fascination of Merrick's visitors) and Dune(the society of Freman existing independent of the source of power on Arrakis). The frolicking of the dog over the injured man is an example of Lynch's use of comedy within tragedy. In Twin Peaks the most dramatic scenes are played for laughs, Leyland going down with the coffin at Laura's funeral (episode 3), the obsessive rearranging of furniture prior to interviewing the rape victim Ronette Pulanski (episode 5). The Lynchian style, the way he constructs each frame, owes a lot to his beginnings as a painter (there is an inordinate attention to detail), and echoes the traditions of silent film. John Orr, in 'Cinema and Modernity', says "Lynch's brilliant vision of contemporary mores is linked, somewhat incongruously, to a style of acting and static mise-en-scene which recall classic Hollywood melodrama and before that the exaggerated gestures of the Expressionist persona of silent film". Colour is used thematically; black and white for Eraserhead and The Elephant Man, red and white for The Grandmother, dark blues and purple in Blue Velvet and earthy greens and browns in Twin Peaks. Wild At Heart's story stems from an incident where Sailor "got too close to a fire", hence the colour scheme is red and yellow, with the passing of time punctuated by extreme close ups of match-heads bursting alight and the tips of cigarettes glowing. Sound is very important to Lynch. Wind, rain, animal roars and electrical humming are used to "paint mood" to scenes. Lynch says, (quoted by Chion) "people call me a director, but I really think of myself as a sound man". Sandy's room is above her father's in Blue Velvet (a film that is motivated by a severed ear), "I hear things" she says, just as the Log Lady's log has "heard things" in Twin Peaks. Variations in speech create effect, Frank shouts in close proximity in Blue velvet just as Bobby Peru whispers seductively and Santos whispers conspiratorially in Wild At Heart when there is no danger of being overheard. The use of speech is particularly sophisticated in Dune, with its whispered inner narratives. Paul's other name, Muad D'ib is discovered to be an animating destructive force when intonated correctly. In Twin Peaks Agent Cooper carries a Dictaphone with which he makes oral notes to his never seen secretary Diane. The ethereal music of Angelo Badalamenti is the soundtrack to Lynch's world, it mixes smoothly with hums and roars around it, as do the whispery vocals of Julee Cruise. Shouts and whispers are not the only contrasted extremes. Lynch's editing loves to juxtapose a sweeping wide angle with an extreme close-up. Even his actors are the extremities of biology - Twin Peaks featured a dwarf and a giant. The way Lynch directs his actors emphasises their rigidity, from Henry's inhibited shuffling to Cooper's upright stance. His first two films both featured Grandmothers that barely moved, as do the waving fireman and the standing corpse at the beginning and end of Blue Velvet. The lady in the radiator performs a minimalist dance pre-figuring Audrey's dance in Twin Peaks which involved swaying on the spot. These rigid bodies are occasionally set afloat, as Henry is in the title sequence, so is our introduction to Laura Palmer, as a corpse floating down the river. Lynch, Badalamanti and Cruise collaborated on an album entitled "Floating into the Night" some of which featured in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks including the theme song "Falling". Falling and floating become motifs, just as Henry floats in the void at the start of Eraserhead, Laura feels she is falling into a void in Fire Walk With Me. In Blue Velvet Dorothy tells Jeffrey she's falling. In Dune the representation is more literal, the navigator being a floating grotesque, as is the Baron. In 1963, Andrew Sarris refined his definition of authorship with the article "Towards a Theory of Film History", in which he states that "Ultimately, the auteur theory is not so much a theory as an attitude, a table of values that converts film history into directorial autobiography". The autobiographical aspect of authorship is unavoidable if it is, as Sarris claims, the director's personality that is being represented in his/her films. If an auteur's upbringing shaped their personality it is logical that it should also shape, or at least influence, their artistic output. Lynch's father was a research scientist for The Department of Agriculture, he investigated tree diseases. This probably explains the multitude of tree/logging references, particularly in Twin Peaks; Coopers opening line in the pilot enquires as to what type of trees grow in the town, the saw mill is of narrative importance and the character of the log lady carries a log at all times. In Blue Velvet the "sound of sawing wood" introduces the town of Lumberton. His mother was a language tutor which may be reflected in the association of women with the alphabet, not just in the short of the same name but in Twin Peaks the victims are found with letters under their finger nails. In an art school project, Lynch submitted a series of paintings in which women turned into typewriters. The director's life experiences must also be influential, according to Richard Corliss, writing for 'Time' magazine, "Lynch says Eraserhead sprang fully formed from nights in that 'crime-ridden' city [Philadelphia]". Two final details to complete the Lynchian perspective are industry and electricity and Lynch's notion of time. Put simply, industry and electricity are good. Electrical hums and industrial roarings are signs of normality. It is only when they are interfered with that problems arise, for example the saw mill is closed in the pilot episode of Twin Peaks. Blowing light bulbs are used to create tension. The climatic scenes of Eraserhead, Twin Peaks (episode 29), and Fire Walk With me all feature electrical strobing. The emblem of Lynch/Frost productions is lit by electrical flashes. Lynch often speaks of his pet project, the as yet unfilmed Ronnie Rocket, which is about "a little three foot guy with sixty-cycle alternating current electricity and physical problems" (quoted by Chion). The industry links with the smoke and steam that colour his films, particularly Eraserhead and The Elephant Man. Lynch has twice produced what he calls "industrial symphonies", once as a series of paintings, second as a show with Badalamenti and Julee Cruise. In Twin Peaks time is slightly abstract. In Eraserhead, Henry's wait for the lift doors to close makes an eternity out of thirteen seconds of screen time. In Dune, Paul's dreams give him access to his future. In Twin Peaks, and especially Fire Walk With me, time has gone haywire. The flowing river over the credits sets the pace for the steady flow of time in the town, this contrasts with the Black Lodge where Cooper and Laura can meet independent of time and space. The red room has the decor of a waiting room. The plot of Fire Walk With Me, bizarrely, is just as valid as a sequel rather than a prequel to the series, and, more bizarrely, most valid as both, with the progression of events across 29 episodes and two hours of film forming an eternal loop. The obsessive references to the time of day and the scene with the temporal and spatial duplicity of Agent Jefferies in Fire Walk With Me gives a clue to this interpretation. Other themes and motifs are the subversion of matriarchy/patriarchy, many characters having 'split' mothers or fathers (the actress replacing the mother and the patriarchal feud of Treves and Bytes in The Elephant Man, Jeffrey's surrogate parents of the psycho and the masochist in Blue Velvet, the home-grown parent in The Grandmother), dogs (feeding in Mary's house, Toto in Wild At Heart, Lynch's comic strip 'The angriest dog in the world'), the number 26 (used as apartment number in many films), the portrait as motif (the mother and the actress in Elephant Man, Mary ripped in half in Eraserhead, Laura the home-coming queen in Twin Peaks) and the image of the woman in the doorway (Mary's introduction in Eraserhead, Perdita's introduction in Wild At Heart, Mrs. Tremmond beckoning from the doorway in Fire Walk With Me and Audrey chained to the door of the bank vault in the final Twin Peaks). The Evolving AuteurOne thing that is hopefully apparent from this analysis of Lynchian themes is that not all were blatant in Eraserhead. For example Twin Peaks's notion of time seems to fit into the world of David Lynch and can be traced back through the previous works, but never before had it been foregrounded. Similarly the notions of the facade of small town life is a very Lynchian quality, and dominates his work post-Blue Velvet, but it doesn't really feature very prominently in his first three films. This could imply one of two things. First that the auteur evolves, new themes emerge and fuse into the director's style; Blue Velvet introduced a second wave of Lynchian attributes compatible with the previous set, Twin Peaks introduces the third stage of evolution. Secondly, it may imply that our thematic and stylistic consistencies aren't as 'consistent' as we first perceived, if the origins of new themes cannot be sufficiently rooted in early work can they be accepted as part of an auteur's oeuvre? The auteur theory relies on the director as a constant factor in a collection of films. If the factor isn't constant it is a lot harder to isolate. This is not to dispute the relevance of the term 'auteur' only to highlight the difficulties in attributing it to a specific director. Sarris came up with a pantheon of definitive auteur directors that caused considerably more debate than his definition of the term. It is unlikely that a list of 'great' directors (and consequently the exclusion of 'non-great's), in accordance with auteur theory is feasible, as it is so subjective. Even Sarris's first premise, that of directorial competence, is a matter of opinion, and the second premise relies on the critic/spectator's ability to discern the personality within the film. In the case of David Lynch, I can only express my opinion that he is a competent director. The second premise, the signature of his personality has hopefully been demonstrated in this chapter. The third premise, the interior meaning or 'Lynchian' quality I cannot be sure to have proved; it is possibly too early into his career to make this definition. Hopefully, with the benefits of time and distance a more precise and simple definition of Lynchian will emerge, a definition that can encompass the many attributes detailed above. So far the most succinct definition I have found comes from David Foster Wallace, writing for 'Premiere' magazine : "An academic definition of Lynchian might be that the term 'refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former's perpetual containment within the latter'. But like post-modern and pornographic, Lynchian is one of those words that's ultimately definable only ostensibly - i.e., we know it when we see it. Ted Bundy wasn't particularly Lynchian, but Jeffery Dahmer, with his victims' various anatomies neatly separated and stored in his fridge alongside his chocolate milk, was thoroughly Lynchian. A Rotary luncheon where everybody's got a comb-over and a polyester sports jacket and is eating bland Rotarian chicken and exchanging Republican platitudes with heartfelt sincerity and yet are either amputees or neurologically damaged or both, would be more Lynchian than not. A hideous bloody street fight over an insult would be a Lynchian street fight if and only if the insultee punctuates every blow with an injunction not to say fucking anything if you can't say something fucking nice."I think the most important word he uses here is "ostensibly", the Lynchian is not something easily defined but it is easily recognisable. |