|

|

|

The Films of David Lynch Authorship and the Films of David Lynch Introduction Chapter 1: Eraserhead Chapter 2: Elephant Man/Dune Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Chapter 4: Wild At Heart Conclusion Matt Pearson 1997 50 Percent Sound Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Conclusion Philip Halsall 2002 Bibliography Resources |

|

Chapter 2 I played 'Crying' and then I played 'In Dreams', and as soon as I did, I forgot 'Crying'.

(Lynch in Rodley, 1997, p.128)

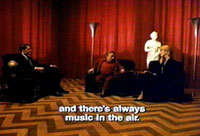

One particular element that has occurred in a number of Lynch's films is singing, that is, a character has suddenly broken into song. In the context of Lynch's films this often comes as quite a surprise, or does it? As I discussed in the previous chapter, dialogue is an extremely important factor in Lynch's films and has been used in various ways to great effect. A character's speech, voice and delivery can create a new dimension for the audience and helps to create diverse textures and moods that cannot be portrayed as effectively with visual methods. So what better way to emphasise a character's speech than letting them sing? It is safe to say that Lynch's films are not musicals in the normal sense, but they do contain an air of fantasy that is remote and abstract yet serves a purpose, a phenomenon that can be seen in musicals. The fact that people burst into song is surreal and entertaining, but the songs do actually serve to enhance the feel of the film and also strengthen the narrative. A person singing a song is merely an extension of the dialogue, but delivered differently. It seems fitting for a director like Lynch, who constantly challenges the use of the voice and dialogue, to use singing in his films. He appears to adopt music and singing in his films in a musical style, to reiterate the narrative, to strengthen characters, but also to subvert the on-screen imagery and visual element of the film. The writer Chris Rodley notes this when he comments, "Not only are his [Lynch] images transformed by the sounds and sentiments of the music, but these images in turn re-invent the music itself twisting its meaning or complicating its often simple, emotive intent until the two become inseparable." (Rodley, 1997, p.125) In Wild at Heart (1990) Lynch takes full advantage of the musical notion and allows for the main character, Sailor Ripley (played by Nicholas Cage), to burst into song not once but twice. On both occasions Sailor sings Elvis Presley songs, the first 'Love Me' and the second 'Love Me Tender', both sung directly to his sweetheart Lula (played by Laura Dern). It is appropriate that Sailor sings Elvis, as it is obvious that the character of Sailor is based upon the young Elvis, with his black hair pushed into a quiff, his southern drawl and his hip-swinging swagger. When Sailor sings he even sounds like Elvis, drawing on his easily recognisable vocal characteristics, further enhancing his role. It is not only Elvis who is referenced to in Wild at Heart; the film is overflowing with references to The Wizard of Oz (1939), which was a musical. The audience is able to witness the analogy between the two films constantly, but it could be argued that Lynch has not only referenced the Wizard of Oz, he has in fact used its musicality to reinforce the narrative of Wild at Heart by allowing Sailor to sing. The writer Barry Gifford who wrote the book Wild at Heart: The Story of Sailor and Lula upon which the film is based, described the film as being, "Like a big dark musical, kind of like an Indian movie." (Gifford in www.geocities) Gifford's comment appears to be an apt description, in that, like Indian films, the songs highlight moments of importance, as is the case in Wild at Heart, but within the context of the film they also come across as slightly comical or farcical. Without resorting to choreographed dance scenes Lynch stretches this comical element further in the film by rendering the on-screen imagery absurd and ridiculous. When Sailor first sings it is in the Hurricane club, a club full of biker types and heavy metal music. A stereotypical rock band - long hair and spandex pants - provides the music on stage and Sailor and Lula are dancing wildly, in particular Sailor who appears to be performing kung fu . Sailor has a fight with a punk who was making advances on Lula and after dealing with him Sailor decides to sing 'Love Me'. The scene is given an absurd twist when the audience comes to realise that the heavy metal group are playing the backing music for Sailor's crooning, and screams continually erupt from unseen adolescents like those heard at an Elvis performance. Furthermore, the people of the club are all swaying in a circle looking on as Sailor performs to Lula who is bathed in a warm yellow light. So why did Lynch choose this surreal performance? When talking of Wild at Heart Lynch said, "I like darkness and confusion and absurdity, but I like to know that there could be a little door that you could go out into a safe life area of happiness." (Lynch in www.geocities) From this statement one would assume that the initial scene in the Hurricane represented darkness through the demeanour of the club, confusion by the punk's advances on Lula and absurdity through Sailor's outrageous dancing. This then comes to a climax when Sailor fights the punk and then launches into his serenade, the serenade being the 'safe life area of happiness'. It is Sailor and Lula's undying love for one another that creates this strange yet poignant moment, incorporating the clientele and band into transfixed onlookers who are witnessing the couple's love. The singing is like an escape from reality and a release into a dream world that transforms everything around it into an abstracted world where there is only love and no darkness. The variety of emotions on display in the scene gives it a roller-coaster feel, violence, love, envy, lust and humour all mix together into a heady concoction that explodes into the surreal rendition of a love song. This crazy potent brew is best summed up by Lula who exclaims, "This whole world's wild at heart and weird on top!" (Hughes, 2001, p.144) When Sailor sings 'Love Me Tender' at the end of the film once again it appears that Lynch has designed the scene as an escape, but not from reality, rather an escape to a realm of happiness . This realm of happiness is marriage and one realises this when Sailor sings 'Love Me Tender', the song that he would only sing to his wife, a fact that he mentioned earlier in the film. Having had his nose broken earlier in the scene by a gang of street punks and then being visited by the Good Witch in a vision who tells Sailor to return to his forsaken Lula, Sailor runs over the tops of cars in a traffic jam until he finds Lula's car and then bursts into song. The absurdity of this rendition is heightened by the scene: a traffic jam, Sailor and Lula's position on the bonnet of the car, and most of all by Sailor's ugly broken nose. The couple's disregard for what is happening around them in the scene heightens their need of an escape, but also displays their absolute love for one another by reiterating the old romantic notion that they only have eyes for each other. When writing of Sailor's broken nose the writer Martha P. Nochimson argues that it embodies the warfare of culture, in that it is an after effect of cultural control, and mixed with the couple's amorous chemistry, an understanding of realism in closure is created (Nochimson, 1997). The surreal scene is mixed with spots of reality and absorbs them, creating a fitting ending for a couple who have been fraught with real problems and have tried to escape from them via their respective subconscious's. Now the real and surreal have collided their dreams can be clarified; Nochimson realises this when she writes, "Sailor and Lula can only find each other in such a moment of hiatus, when nature and culture are completely balanced." (Nochimson, 1997, p.66) The final song is the icing on the cake, a realisation and fulfilment for Sailor and Lula and perhaps the most 'musical' performance Lynch has offered his audience. Like in a musical the song is the happy ending before the curtain falls and shows Lynch's compassion , but with his trademark twist of visual absurdity. In Blue Velvet (1986) Lynch's use of visual subversion during the performance of the songs was a little subtler than that in Wild at Heart. The first and most vital song performed is 'Blue Velvet', sung by the character Dorothy Vallens who is played by former model Isabella Rossellini . Her character's physical appearance is quite odd, in that she wears very heavy make up, which gives her a strange doll-like face, and this is topped off by a huge unattractive bush-like wig. The critic Michel Chion comments that her heavy make up gives her the look of a poisonous flower (Chion, 1995). It is almost as if Lynch has tried to get rid of some of her beauty and created a mask of sorts, a mask that covers and protects her real identity. Dorothy Vallens' performance and rendition of 'Blue Velvet' is forlorn and sensual, but almost rendered absurd by her physical appearance. The writer Martha P. Nochimson argues that, "The spectacle on stage of the Slow Club when Dorothy sings is a construction of glamour that transcends its almost laughable artificiality and makes accessible to ordinary people (i.e., a mass audience) another level of reality." (Nochimson, 1997, p.111) I agree with this argument, but I feel that her on-stage persona serves to disguise the horrific events and mental anguish that she is experiencing in her life. When she sings it is almost as if she is bereaving; the sadness is evident, but at the same time she exudes an air of sensuality and sultriness. By depicting Dorothy in two various ways in the film, one as a deeply disturbed sado-masochist bereft of her husband and child and the other as a glamorous club singer, Lynch was able to use her singing as a distinction between her two very different lives. Later in the film a different song was used to create a similar sort of distinction between a character's identity that was achieved with 'Blue Velvet' and Dorothy. Frank Booth is the nemesis of the protagonist of the film, Jeffrey Beaumont, and could be considered to be evil personified. At no point in the film does Frank display any sign of kindness or goodness of any description. He fights, swears continuously, deals drugs and generally portrays himself as having no morals whatsoever. Like Dorothy, Frank has a signature tune of sorts that displays Frank in a different way from his regular talking persona this song is Roy Orbison's 'In Dreams' . But 'In Dreams' also serves to narrate the situation Jeffrey has landed himself in, albeit in a slightly abstract manner. Nevertheless the audio and visual relationship on-screen gives the audience some understanding of the horror Jeffrey is being subjected to. Lynch lends a surreal and strange air to the rendition of 'In Dreams' by having it performed by an odd character called Ben who appears to be a close friend of Frank. Ben is an effeminate and flamboyant looking person who seems to be the exact opposite of Frank, but on closer inspection could be interpreted as a more sinister and calculated individual when he punches Jeffrey. When he performs 'In Dreams' Ben does not actually sing the song but mimes to a tape using an industrial flashlight as a microphone. The huge torch and words of the song become symbolic of the surreal situation Jeffrey finds himself in. The critic Kenneth C. Kaleta confirms this argument when he writes, "The lyrics about reality and illusion in love take on new meanings in the context of the film. However, the lip-syncing and grotesque staged lighting of Ben's version immediately colour its use. In fact Lynch succeeds in moulding the music into an anthem in the film for secrets within each of us." (Kaleta, 1993, p.124) The critic John Alexander has argued that the detached absurdity of the scene portrays an otherworldness by which Jeffrey finds himself separated from reality (Alexander, 1993). I agree with this argument and feel that a similar effect of otherworldness is achieved with Sailor's renditions of Elvis Presley songs in Wild at Heart, as noted earlier. But where Lynch used the song in Wild at Heart as a metaphor for escape, 'In Dreams' appears to be a metaphor for Jeffrey's present captivity. The audio and visual relationship is similar between the two films' use of songs, but has been twisted and turned back on itself like a mobius strip. Lynch's adoption of singing enhances the emotions of characters; it defines who they are visually, but also peels back layers and allows the audience to take a deeper look into their subconscious. The songs capture the spirit of the films, but as the films are not musicals, the songs feature as an abstract quality within the framework. But they are an abstraction that clearly helps to define the narrative, allowing Lynch apparent moments of weirdness to form a non-linear narrative that actually gives a greater understanding of the overall framework of the film. |