|

|

|

The Films of David Lynch Authorship and the Films of David Lynch Introduction Chapter 1: Eraserhead Chapter 2: Elephant Man/Dune Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Chapter 4: Wild At Heart Conclusion Matt Pearson 1997 50 Percent Sound Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Conclusion Philip Halsall 2002 Bibliography Resources |

|

Chapter 3 I never got deep into working with a composer and having that experience of being able to fall into the world of music, and Angelo invited me into that world, and encouraged it, and many great experiences have come out of that.

(Lynch in www.geocities)

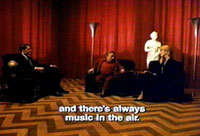

"Magic happened with Blue Velvet, because a sound was created." (Badalamenti in www.lynchnet...abcloseup) So says long time Lynch collaborator Angelo Badalamenti whose name and compositions are now synonymous with Lynch's films. Their collaborative efforts began in 1986 by an accident of sorts with Lynch's Blue Velvet, a film that explored the darker under-belly of white picket-fenced America. The musical score created by Badalamenti to compliment the film was so successful that Lynch has collaborated with Badalamenti on all eight of his major projects since Blue Velvet. The Blue Velvet score created a haunting, dark and sinister atmosphere that clung to the fabric of the film. Badalamenti describes it thus, "It is not the top melody or even the bass, it is something in the middle that kind of rubs wrong, and is maybe even mildly dissonant. You hear it, but it is not in your face." (ibid.) Like Lynch's film, Badalamenti's score contains an almost hidden depth or concealed dimension . The way in which the film begins almost light-heartedly, and steadily progresses into a seedy, sado-masochistic murder mystery, is reflected in the film's score. The critic John Alexander realises this when he writes, "The haunting soundtrack accompanies the title credits, then weaves through the narrative, accentuating the noir mood of the film." (Alexander, 193, p.93) Although the film is underpinned by Bobby Vinton's version of 'Blue Velvet' and Roy Orbison's 'In Dreams', these songs are instrumental to key scenes, as opposed to the score that is evident throughout the film. It is the score that conveys and unites the split persona of Dorothy Vallens, the pervading darkness and evil of Jeffrey Beaumont's nemesis Frank Booth, and it is the score that reflects the two different worlds the audience is subjected to. This argument is noted by the writer Merle Ginsberg who argues, "With Blue Velvet, Badalamenti found the key to Lynch's creative process. The premise is: everything has two sides, and what's underneath the surface is much more interesting than what is on it. And Lynch's process is simply: mood. He knows what aura he wants to present and then he conjures visuals and music to it." (Ginsberg in www.lynchnet...movies90) It is the extra dimension of the score that allows the film's themes to be carried, not as a narrative, but as a catalyst in order to exert the audience's perception of what is taking place. As the sound design of Lynch's films introduce an extra dimension to what the audience perceives, so too do Badalamenti's compositions. It could be argued that film scores in general only serve to create atmospheres and generate feelings, but I would argue that Badalamenti's scores provide something extra. They create themes for characters, which then become ingrained on the viewer's audio perception and symbolise different aspects of what the audience is viewing. The eerie ambience of his pieces give an ethereal and dream-like quality to the films, creating an air of tenderness, but also a feeling of intense depth, an otherworldly undercurrent. These elements are particularly prevalent in Lynch's Twin Peaks where Badalamenti's score becomes as symbolic as the characters themselves. When writing of Twin Peaks the writer Martha P. Nochimson argues, "In early Twin Peaks music is used to underline the tension between the energy in the characters and the stereotypes that only seem to define them. So the music does not in the usual way, classify the characters rigidly but instead becomes another meeting between social constructs and the larger energies." (Nochimson, 1997, p.84) Nochimson's argument goes some way to explain the complexity of the relationship between the characters and the musical themes in Twin Peaks, in that she helps to define a correlation between the characters' lives and secrets on-screen, and the varying use of similar musical motifs to very different effects. In the film Laura Palmer's Theme is used in various situations to opposite effects because of its changing feeling . When Lynch asked Badalamenti to write the song he said, "It should start with an anticipatory melody, then build slowly up to a climax - a climax that's slow and tears your heart." (Lynch in www.lynchnet...movies90) The resulting effort was a piece of music that could be used in many different scenes ranging from dark and brooding to beautiful and love filled. The ambiguity of the music allowed for Lynch to use the theme as a motif for many situations and characters not just for Laura Palmer, and also it helped to twist the meaning of the music associated with the characters. Like Blue Velvet's score, Twin Peaks' helped to create that extra dimension to elucidate certain under-tones of what was happening to or with the characters. The music carried the narrative but played with it too, often creating juxtaposition with the on-screen imagery within that scene. It could be argued that this almost abstract use of music was integral to the overall feel of Twin Peaks with its ability to float between scenes and highlight them as though a character itself. The critic Michel Chion feels that the music is a stroke of genius, in that it fills the film with energy and lets it flow (Chion, 1995). Indeed the music of Twin Peaks when heard can be as identifiable as its visual motifs; black coffee, cherry pie, the log lady and Agent Cooper, and serves to remind people of the curious world that was Twin Peaks. It can be best summed up by the Man from Another Place character when he stated, ""Where we come from ... there is always music in the air." (www.ktepi) One cannot help but feel that the extra dimension of Badalementi's scores gives Lynch's films wholeness, like the final piece in a jigsaw puzzle, albeit a difficult and intricate three-dimensional puzzle. It could be argued that those of Lynch's films that are devoid of Badalamenti's musical input are lacking a certain something, but on the other hand Lynch's films pre-Badalamenti are each very different. Eraserhead's use of sound as a film score worked perfectly and The Elephant Man's film score was chosen by the producer not Lynch, whilst Lynch's choice of the rock group Toto for Dune (1984) was questionable, but ultimately proved fruitful considering how badly received the film was. It appears that the musical relationship between Badalamenti and Lynch, which was established on Blue Velvet and carried through to the present, has established a strong and effective link between the visual and audio vision of David Lynch. Badalamenti's music is instantly recognisable in each and every Lynch film and serves to enhance the visual feast laid before the audience without being too dominant. When Lynch talks of Badalamenti he comments, "He's got this musical soul, and melodies are always floating around inside. I feel a mood of the scene in music, and one thing helps the other, and they both just start climbing." (Lynch in www.geocoities) This notion of climbing could certainly be attributed to Lynch's films, where the audience often finds themselves climbing and falling through complex plots not unlike the scores that accompany them. In particular the score for Lynch's Lost Highway clearly reflected the tumultuous plot that meandered and undulated from start to finish, although like Lynch's Wild at Heart (1990), original songs from various artists were used throughout the film. But the original dark and noirish music composed by Badalamenti formed the backbone of the film's audio content, even being altered with and incorporated into the sound design of the film . This was done when Lynch experimented with recording techniques at the studio of the Film Symphony Orchestra of Prague who performed Badalamenti's score for Lost Highway. The writer David Hughes explains, "Lynch experimented with recording techniques, just as he had during his innovative sound work on Eraserhead, placing microphones inside bottles and lengths of plastic tubing to try and capture a unique sound." (Hughes, 2001, p.211) It is interesting to see how Lynch has managed to combine music and sound design in this way, and it is particularly poignant that he has been able to adopt Badalamenti's music and subvert it in order to produce sound effects. It appears to be the negative of Lynch's notion of sound effects being used to create a musical score; here music is creating the sound effects. The drones and pervading darkness of Badalamenti's music in Lost Highway seem to be a departure from his orchestral themes and sweeping synthesizer orientated pieces of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. Instead it appears Lynch's experimental recording techniques have dispersed Badalamenti's music and transformed it into a texture that clings to the on-screen imagery. Lynch describes it as having a modern noir feel it to it (Rodley, 1997). Scenes of darkness within the character Fred Madison's home are given extra depth by the malevolent drones of Badalamenti's subverted score; they act texturally as an accompaniment to that particular scene . Lynch describes this process thus, "When you see your picture you start building sounds that amplify a mood that has already started, and then when all the elements are together the thing jumps and it becomes kind of magical." (Lynch in Pretty as a Picture, 1997) It appears obvious from Lynch's description that the sound and music acts as a unifying element in the production of his films, but it is also his unique relationship with Badalamenti that has helped to create this magic. Lost Highway is an example where Lynch and Badalamenti have collaborated musically, but have ended up with a soiree into sound design, which enforces Lynch's notion of sound effects as a musical score, but also makes Lost Highway unique. The lack of a Badalamenti musical motif in some way generates a new emotion for those familiar with Lynch's films, in that the ear will be more aware of something missing, which allows the pre-existing songs used in the film to be heard with full effect. For example David Bowie's 'I'm Deranged' (used at the beginning and end of the film) appears to be an ode to the plight of the film's protagonist, Fred Madison, whilst 'Song to the Siren' by This Mortal Coil highlights superbly the passion and mystery between Alice and Pete . But throughout the film it is Badalamenti's abstract and subverted pieces that convey the overall mood of the film and carry the twisted narrative. Where Lost Highway experimented with Badalamenti's compositions and used them subtly as part of the sound design, Mulholland Drive (2001) allowed his music to come to the forefront once again as it had in previous films. Badalamenti's score encompasses boogie-woogie, jazz, orchestral pieces and his trademark sweeping synthesizer soundscapes a la Twin Peaks. The opening Glenn Miller style 'Jitterbug' contrasts heavily to the dark, brooding soundscape of the film's main theme that follows and is a fantastic metaphor for what the viewer is about to be subjected to. In Lost Highway Badalamenti's music had been enhanced to give it a darker edge, but in Mulholland Drive the music is prevalent as itself, not just as an element of the sound design. It manages to mix and glide between these moods subtly without startling the audience, as though it is being injected softly into the film and filtered out just as softly. The music could in fact be interpreted as sound design, but I would argue that it is used as a structured companion that encompasses the entire scene, as opposed to being used to highlight a particular moment. The darkness of the music often seems to be used in contrast to the on-screen imagery, in that scenes set in the 'relative safety' of daylight have an under current of eerie and suspense-filled music, creating a tension Lynch used to great effect in his Twin Peaks series. Badalamenti feels that his use of low instruments - basses, bassoons and clarinets - helped to create a lot of the mood in Mulholland Drive, an effect he refers to as, "Giving you something to turn firewood into flames, to warm your soul." (Badalamenti in www.lynchnet...abcloseup) Mulholland Drive could be seen as a chance for Badalamenti to return to his Twin Peaks overly dramatic sweeping style. Indeed many critics have aired this opinion when reviewing the soundtrack, but I would argue that his score serves as a subtle linear narrative. When compared to Twin Peaks, Mulholland Drive's score lacks the anthem-like themes in Twin Peaks, instead it opts for a field of sound that breathes and envelops scenes like a foreboding unseen presence . Badalamenti describes what Lynch wanted from him, "He wanted me to do that for the main title, but for it to be beautiful at the same time. David asked for it to be used at different places and in different ways in the film, to come back like a good old friend. He wanted the audience to relate to the main theme, whether they'd realize it or not." (Badalamenti in www.filmscore) This idea of a reoccurring yet ever changing use of a musical motif draws parallels to Lynch's notion of recognition and identity in Mulholland Drive. Characters appear to swap their names and lives as the film progresses, yet at the same time they are recognisable and established as a completely different persona. The music echoes this metamorphosis by engaging the viewer through the recognisable strings and synthesizers adopted by Badalamenti. But it also evolves and changes, albeit a little more subtly than the characters, into a dark, brooding menacing atmosphere that, more often than not, reflects the anguish of the characters. From Blue Velvet to Mulholland Drive, Lynch and Badalamenti's collaborative efforts have been an integral part of the overall make-up of Lynch's film projects. The scores have supported and strengthened Lynchian notions in filmmaking and they have often provided a subliminal narrative to the abstract images that the audience is subjected to. Perhaps Lynch sums up Badalamenti's importance best, "Lately I feel films are more and more like music. Music deals with abstractions and, like film, it involves time. It has many different movements, it has much contrast. And through music you learn that, in order to get a particular beautiful feeling, you have to have started far back, arranging certain things in a certain way. You can't just cut to it." (Lynch in www.geocities) |