|

|

|

The Films of David Lynch Authorship and the Films of David Lynch Introduction Chapter 1: Eraserhead Chapter 2: Elephant Man/Dune Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Chapter 4: Wild At Heart Conclusion Matt Pearson 1997 50 Percent Sound Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Conclusion Philip Halsall 2002 Bibliography Resources |

|

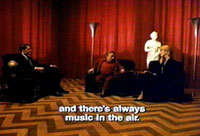

Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Post-modernism and AuthorshipDavid Foster Wallace, writing for 'Premiere' magazine, says "The word post-modern is admittedly overused, but the incongruity between the peaceful health of his mien and the creepy ambition of his films is something about David Lynch that is resoundingly post-modern." Although the tag could easily be applied to any of his films in this chapter I'll take Blue Velvet as my example. This film was Lynch's return to form following the failure of Dune, the story-line centres upon Jeffrey, a college student who discovers a severed ear. His interest in the mystery associated with the ear draws him into the world of Dorothy Valens, a night-club singer, whom it turns out has had her husband and son kidnapped by a gas-snorting psychopathic gangster named Frank Booth, the severed ear belonging to her husband. Eventually Jeffrey is forced to confront Frank. There is also a sub-plot concerning Sandy, the detective's daughter, whom Jeffrey falls for in the process. This chapter aims to discuss to what extent Lynch's post-modern representation is compatible with Lynch the auteur. To define the post-modern aesthetic and see how it applies to Blue Velvet I need first to break it into its component elements. Susan Hayward, in 'Key Concepts in Cinema Studies', defines it thus; "the post-modern aesthetic relies on four tightly inter-related sets of concepts ; 'parody and pastiche', 'prefabrication', 'inter-textuality', 'bricolage'." Post-modernism, as Lyotard defines it, also implies a blurring of high and low cultural boundaries, the inability to distinguish between the 'real' and the artifice, the commodification of everyday life and the sense of the fragmentary, ambiguous and uncertain nature of living. To these features I would add heightened social and individual reflexivity, ironic self-referentiality, the de-differentiation of classical western categories, the questioning of meta-narratives and the concepts of the French Cinema du look, that of emphasised style - the fetishisation of the image. The four concepts Hayward mentions can be grouped together under the heading 'inter-textuality', they all refer to the recycling of images from the past, assembled together in the form of bricolage. She says "the visual arts see the past as a supermarket source that the artist raids for whatever s/he wants". We can see how this is done with the use of film noir in Blue Velvet. The appropriation of the genre is pastiche rather than parody as it simply lifts the imagery without subverting it. The ideas of small town innocence borrow heavily from Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt, the opening heart-attack sequence refers to the LumiÈre brothers' L'Arroseur Arrose(1896). The Badalamenti score seems derivative of the music in Experiment in Terror (Blake Edwards 1962), a film set in a suburb called 'Twin Peaks' (Twin Peaks also featured heavy 'borrowing', with specific references to Preminger's Laura(1944), Hitchcock's Vertigo(1958) and Robert Wise's Born To Kill(1947)). Less specific 'borrowing' occurs with generic chronotypes such as the smoky night-club and the teen movie coffee-shop. Timothy Corrigan, in 'A Cinema Without Walls', describes Blue Velvet as "a pastiche of too many distinctive generational images (from the fifties through the eighties) made oddly familiar by the rapidity with which the distinctions decay and meld together in this temporary place". Lynch, talking about Wild At Heart in 'Time' magazine, said "See, I love 47 different genres in one film. And I love B-movies. But why not have three or four B's running together? Like a little hive!", i.e. he favours a de-differentiation of classic western categories. So what is the purpose of utilising these pre-fabricated images? The image can bring with it the meaning or convention of its source. It can be subverted in parody, such as Bobby Peru as an ironic Clark Gable in Wild At Heart, or it can be quoted in pastiche, what Jameson calls 'blank parody'. With pastiche the references are reduced to nothing more than a clichÈs, overly familiar with the viewer. Blue Velvet doesn't pastiche any particular film-noir but film-noir as a genre. Umberto Eco, in 'Travels in Hyper-reality', sees a profusion of clichÈs providing pathos, he says, "when all the archetypes burst out shamelessly we plumb Homeric profundity. Two clichÈs make us laugh but a hundred clichÈs move us because we sense dimly that the clichÈs are talking amongst themselves, celebrating a reunion." In Eco's view it is unnecessary to be aware of what each individual reference is to, it is just necessary to know that these are clichÈs and that by locating the film in a long cinema tradition it creates a 'cosiness' for the viewer. The inter-textuality, as well as referring to genre, is often more specific, a self-referential inter-textuality to Lynch's own previous work. In the first chapter, by defining the Lynchian attributes and seeing how they feature across all his films we can see that the films are linked by inter-textual references to each other. Self-referential inter-textuality is a consistency of motif that forms part of the definition of 'auteur'. Therefore, for inter-textuality, self-referentiality and reflexivity to be a post-modern traits, it would seem post-modernism supports the auteur theory. It seems easy to take any of the post-modern elements defined and apply them to the work of David Lynch. Jeffrey becomes aware of the fragmentary nature of his existence, he tells Sandy about the house where "a kid with the biggest tongue in the world lived ... but then he moved away", Timothy Corrigan, in 'A Cinema Without Walls', says "What Jeffrey learns by the end of the movie ... is therefore the most contradictory of knowledge: that this neighbourhood is made up of nothing more than fragmentary images that were once meaningfully distinct and motivated but which continuously lose these meanings because they are always in the process of decaying into sameness."I intend to leave the commodification theme until Wild At Heart but a questioning of meta-narratives is apparent in his subversion of cinematic form and genre. Blue Velvet has a closing sequence that parodies many cinematic standards. Robin Wood, in 'Hitchcock's Films Revisited', says "the final sequence is the conventional closure of classical narrative, once again foregrounded as clichÈ", order is restored, the return of the father re-establishes a patriarchal hierarchy, Dorothy is 'cured' of her sadomasochism and the heterosexual couple of Sandy and Jeffrey is constructed. But, the mechanical robin tells us, it is a "representation" rather than a "presentation" of reality, it is hyper-real, a mockery. In 'Post-modernism as Humanism', Scott Lash says "the logic of post-modernism inheres in its problemization of the reality". One particularly prominent theme throughout the film, and of Lynch's work in general, is that of dreams. Dreams are constantly referred to; Frank and Ben both sing 'In Dreams', Sandy describes her dream of the robins to Jeffrey, Jeffrey relives his experiences in a dream sequence and all the main action takes place at night ("Now it's dark" as Frank says). But as well as being a recurring theme this could indicate we are to interpret the whole film as Jeffrey's dream. The film starts with a surreal sequence of small-town imagery; the fire-truck, the picket fence etc., Jeffrey's father has a heart attack, Jeffrey goes to visit him in hospital and on the way home discovers a severed ear which he takes to the police. Later that night he tells his mother and aunt (who are watching a suspense film on TV) that he is going out for a walk. We then have a long shot that slowly zooms into the ear. If we regard this as prologue, the final scene in the garden becomes epilogue, it begins with a similar zooming shot out of an ear that turns out to belong to Jeffrey. He awakens on a sun lounger in his garden. This forms a Wizard of Oz style narrative structure, in which the Oz story is a dream experienced by the protagonist Dorothy (note also that Lynch's next film Wild at Heart has a Wizard of Oz theme expressed more explicitly, discussed in chapter 4). Therefore, we can say that a film-noir fantasy begins going in one ear and ends by coming out of another, implying it all exists in Jeffrey's head. As Frank tells Jeffrey in song, "we're together in dreams". Notice how Sandy emerges from the dark just as Henry's neighbour did in the dream sequence in Eraserhead. As with The Wizard of Oz we can see elements that may have inspired parts of the fantasy in the prologue and epilogue section, e.g. the robins and the suspense film. If we accept this as our reading of the film we can compare the 'fantasy' with the 'reality' on a stylistic level. The opening and closing scenes have a very surreal quality; the slow motion rhythmic waving of the fireman, the mechanical robins etc.. The scenes are colourful and brightly lit, even the father's heart attack is treated with comedy. This contrasts with the dark world of the fantasy where the main events all happen at night (the day's events are skipped over briefly) in gloomy settings. The stylistic elements of the fantasy we can relate to the suspense film that was showing as Jeffrey left the house and the external diegetic music that accompanied the scene. Lynch describes Blue Velvet as a story about a guy "who lives in two worlds at the same time, one of which is pleasant, the other terrifying". But the suggestion is, contrasting the surrealism of the opening and closing with the grim realism of the fantasy, that Jeffrey's reality is more 'unreal' than his dream. The robin in Jeffrey's garden is mechanical, we are reminded it is a film we are watching, the whole piece is a simulacrum of reality, it is hyper-real in Baudrillard's sense of the word, but for Jeffrey it is the only reality, he is a fictional character. Hayward, in 'French National Cinema', says "Post-modernity implies the rejection of history or, rather, the disappearance of a sense of history." Blue Velvet is very ambiguous as to its temporal setting; the locations and characters are from the 1950's, the stylistics are from the 1940's, the themes are from the 1980's. Corrigan says : "Lynch's neighbourhoods have always been built on a familiarity that stubbornly and violently refuses the comfort of psychological or historical meaning. What disturbs about Eraserhead, Elephant Man, Dune and Twin Peaks is a shared preoccupation with historical evaporation of social or psychological meaning beneath a surface of seemingly normal places, things, and people, an evacuation that leaves only grotesque shells. The nostalgia of Elephant Man is for some meaningful human presence under the skin of a boy encrusted with inhuman deformities; in Dune these physical and social distortions of humanity's search for their redemptive substance in the excrement of worms, the only presence underneath a desert world. In each case, the past and the future contend for the same place, a historical reality that, missing any kind of depth of historical spirit, becomes only a violent collection of images and clichÈs in search of stability and meaning. In Jameson's words about the historical 'aimlessness' of Blue Velvet and Something Wild(Demme 1986), they 'show a collective unconscious in the process of trying to identify its own present at the same time that they illuminate the failure of this attempt, which seems to reduce itself to the recombination of various stereotypes of the past' ('Nostalgia for the Present' 536). 'I don't know what a lot of things mean,' Lynch blithely claims (Bouzereau 39)."What this is saying, simply, is that Lynch's world is shallow, a world of mechanical reproduction. This is acknowledged with the mechanical robin in the final sequence; the metaphor of love within the film is revealed to be a cheap prop. The film is questioning its own ability, and hence the ability of cinema as a medium, to represent life, reality and concepts such as love and evil (Jeffrey armed as a bug-sprayer is all that is required to combat the metaphor of evil, the bugs from the opening sequence). This problemization of reality Corrigan further observes in the way the "characters communicate through advertising slogans". Robin Wood points out that Sandy's speech about love "is written not as an expression of innocent faith but as a parodic reduction." It is spoken in front of a church, but there is no religious content to film, it is purely a symbol, "a signifier without substance". The 'In Dreams' sequence is the epitome of this representation of reality; Ben sings over a tape, a performance of a recording of a performance, a "double removal from natural expression" (Corrigan). Lynch, often inaccurately branded a surrealist is more appropriately a 'hyper-realist'. Fred Pfeil, in 'Home Fires Burning', says "simultaneously hyper-realising and decentering narrative is what Blue Velvet is about", he goes on to quote Michael Moon who talks of "the fearful knowledge that what most of us consider our deepest and strongest desires are not our own, that our dreams and fantasies are only copies, audio and video tapes, of the desires of others and our utterances of them lip-synching of these circulating, endlessly reproduced and reproducible desires." This self-conscious referring to the mode of production, is also compatible with the dream motif, cinema is often likened to dreaming. Jeffrey's problem with reality stems from the fact that his reality is hyper-real, more 'reel' than 'real', hence the film's stylistics are deeply rooted in film tradition. As Corrigan says Blue Velvet attempts to "address a contemporary audience according to their own communicative formulations." The style of Blue Velvet fits into the Cinema du look tradition. These films are usually categorised as being very spectacular visually, favouring style over content, close relatives of the music video, advertising and comic books (see Wild At Heart's pop video aesthetic), quoting other films (as discussed above) and a focus on youth. The film obviously focuses on youthful protagonists and as discussed Jeffrey's world is very unreal. This denaturalisation functions to distance the spectator, it draws attention to the means of representation, the mode of production. By doing this it makes the viewer more analytical of the text as they watch it. The camera work also emphasises this self-referentiality. It highlights 'the gaze', the idea of the protagonists being watched; by voyeurs, by Lynch as director and hence by the cinema audience. An example of this is Jeffrey hiding in the closet to watch Dorothy undress, the audience is complicit in Jeffrey's perversion. This also features in Eraserhead and The Elephant Man, the audience has to ask themselves whether they are detective or pervert. Whereas modernism was about production and consumption, post-modernism emphasises reproduction and re-consumption. It implies a move away from the modernist Auteur theory towards a more textual analysis, the meaning of a text lying not in its construction but in its interpretation by the reader. I've referred to the film as Jeffrey's story because the film establishes it is to be viewed subjectively from Jeffrey's point of view (just like we experienced Henry's view of reality in Eraserhead). By establishing this it creates further ambiguity in the plot, we are left to speculate as to how much of the story is the product of Jeffrey's imagination. This narrative ambiguity, temporally, textually and subjectively, is typically post-modern and again has structuralist leanings. As Corrigan states, "so called post-modern films can now be seen addressing viewers across formulation that subvert, deflect, or minimalize the very activity of filmic reading". Robin Wood points out two possible readings: "the spectators [of Blue Velvet] seem about equally divided between those who believe themselves to be laughing at the film and those who believe themselves to be laughing with it. (it is possible to argue that the film is laughing at both categories). In fact, Lynch operates a double standard throughout ... The presentation of 'normality' (the 'innocent' heterosexual couple, their small town suburban family backgrounds) can be taken absolutely straight by the more naÔve members of the audience (those poor shmucks) or as wittily and hilariously 'knowing' by the more sophisticated."As Borges said, "it's much more difficult to be a reader than a writer". For post-modernism to imply structuralist readings of texts, and structuralism to be considered an opponent of auteurism, it follows that one of two things can be occurring; either post-modernism contains an inherent contradiction in supporting the auteur theory, or it supports the compatibility of structuralism and auteurism Wollen proposes (as discussed in Chapter 2). It is in the reflexivity to cinema production that causes problems with some critics (see the "phoniness and fakery" criticism of Wild At Heart in chapter 4). The auteur seems less of a mystic presence when the representation process is foregrounded, the wiring under the board displayed. To be an auteur and play with ideas of cinematic representation is to have one's cake and eat it. This demands a new type of auteur, stripped of mystic trappings (free of Sarris's third premise), which emerges with the commodification of authorship in chapter 4. Robin Wood says: "the 'vision' of Blue velvet, while indeed personal, also belongs very much to its period, and the phenomenon of the film's critical success cannot be explained in simplistic terms (what Richard Lippe calls 'bastardised auteurism'). The personal vision, the way it expresses itself, the way it is received, the almost unanimous critical adulation, have all to be understood in relation to a particular phase of cultural development ... Lynch's fireman beaming at the audience from his itinerant fire-wagon is merely ridiculous, a clichÈ rendered laughable, introducing the tone of parody/pastiche that immediately locates the film within the era of Postmodernism."This means that by locating any one of Lynch's films within post-modernism it is acknowledging the influence of social and ideological location upon the text, the structuralist approach. We could also bear in mind its more specific temporal origin; the zeitgeist of the mid-eighties when the film was released. Many films of 1985 and 86 had comparable themes, for example Martin Scorsese's After Hours, Susan Seidelman's Desperately Seeking Susan and the aforementioned Something Wild. Blue Velvet could be pigeon-holed with these as they all dealt with middle class escapism and the darker side of contemporary life. So, as I have established, post-modernism implies both structuralism and auteurism. Therefore, to be a post-modern auteur, the auteur theory has to be compatible with structuralism and vice versa. So long as structuralism is compatible with the auteur theory, as Peter Wollen proposes, auteurism can also be compatible with post-modernism. |